I was deeply saddened to learn that the brilliant and warm-hearted Reuven Tsur passed away earlier today. His contributions to the linguistics of poetry–including the study of literary universals–were invaluable. The Literary Universals Project was honored to publish his and Chen Gafni’s “Phonetic Symbolism: Double-Edgedness and Aspect-Switching” just two years ago. This is a great intellectual and human loss.

Author: Patrick C. Hogan

Universals and Mythology: An Interview with Dr. Wendy Doniger

Conducted by Arnab Dutta Roy.

(Housed off-site; available through the following link: Universals and Mythology.)

Evolution and Literary Universals

Steven Pinker, Harvard University (and Patrick Colm Hogan, University of Connecticut)

An extended interview with Steven Pinker by Patrick Hogan, housed off-site and available through the following link:

Evolution and Literary Universals: Steven Pinker (and Patrick Hogan).

Counterintuitive Imagery as a Narrative Universal

Tom Dolack, Wheaton College

It has been postulated that religious beliefs “minimally violate ordinary intuitions about how the world is” (Atran, In Gods We Trust 83). This is not to say that religion need be defined by counterintuitive imagery. There is a constellation of behaviors that has been proposed as underlying religion including a “hyperactive agency detection device” (Guthrie), overpromiscuous Theory of Mind, and ritual practices. Nonetheless, counterintuitive imagery appears to be a religious universal. Some research on this topic has noted that counterintuitive imagery is not a priori religious. Specifically, Kelly and Keil have looked at Ovid and the Brothers Grimm; Burdett, Barrett, and Porter have looked at folktales; and Swan and Halberstadt have more recently examined what differentiates religious from fictional counterintuitive agents. Even so, work in the field has mostly focused on the religious domain. What I propose is a research program that explicitly applies insights into religious counterintuitive imagery to narrative more broadly, including modern literature. This is in keeping with the idea that cognitive “templates” for religious concepts, discussed by Pascal Boyer (Religion Explained 78), have application in a wide variety of cultural artifacts.

Art was once thought to be the sole province of Homo sapiens, a cultural Rubicon that only we crossed. But, as has often been the case in recent years, the archaeological record shows that we are not so special. Intentional markings have been found on mussel shells dating back a half million years, which would make the suspected artiste Homo erectus (Joordens et al.). Whether we wish to term these engravings “art” is open to debate, but they seem to be intentional, serve no apparent utilitarian function, and are not random. If not art, then what? Doodle, perhaps, but that would probably be distinction without difference in this context. Our cousins the Neanderthals clearly also “doodled,” as evidenced by cave art in Spain predating the arrival of Homo sapiens (Hoffmann et al.; Hawks). Examples from our own direct ancestors are widespread and found all over the world (Henshilwood et al.; Aubert et al.). But much of the art we find in the record can be described as decorative or mimetic. The type of symbolism or figurativeness we associate with the term “art” in modern times, not to mention with human behavior more generally, is clearly a more recent addition.

Along these lines, the Löwenmensch or Lion-Man, found in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave in Germany, stands out. Not only is it one of the oldest, if not the oldest, statuette on record; it is also conspicuously not abstract, mimetic, or purely decorative. About a foot in height and carved from a mammoth tusk, the largest piece of the figurine was unearthed in 1939 (smaller pieces were dug up later and the pieces painstakingly reassembled). The Löwenmensch has a human body, with the head of what appears to be a lion. It is unclear if the figurine was meant to be symbolic or religious (theories abound), but it is clearly figurative. Nobody ever saw such a creature. It is all too easy to lose sight of how revolutionary this would have been. It would be unexceptional today in our world of CGI; it would have been unexceptional even thousands of years ago when mythology and tales around the campfire were commonplace. But there was a time when such a hybrid creation was entirely new, and it changed human culture forever.

We don’t know when or where this capacity for imagining hybrids originated, and can only hypothesize about how it came to be (changes to our mental architecture along the lines of Mithen’s “cognitive fluidity”? A tipping point in cumulative cultural evolution?), but however this change occurred, it signals a new ability to envision what did not and could not exist; previously we could either reproduce what we had seen or heard about or make abstract shapes that we found pleasing.

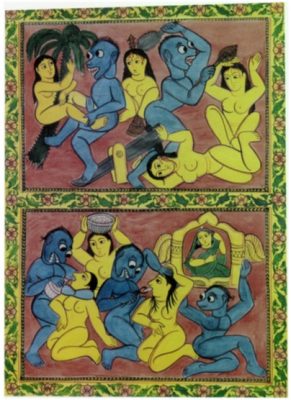

I suspect it is no coincidence that this oldest of all figurative art is a hybrid. Such hybrids are a stock element of religions, mythologies, and folklores the world over. The technical term for them is counterintuitive imagery. What makes these images special is that they violate our natural intuitions. We have innate ontological categories (Atran,“Basic Conceptual Domains”) in our minds such as animal, person, inanimate thing, tool and plant. Each of these categories involves specific expectations regarding our innate knowledge domains of physics, biology, and psychology. A natural object such as a rock does not move on its own, does not grow or reproduce, and does not think. An animal does move on its own, grow, eat, and reproduce, has some mental workings, but does not speak. Humans are like animals biologically, plus have additional psychology faculties, but are restrained by certain physical laws (we can’t fly or walk through walls). Counterintuitive images violate these ontological expectations in one way or another—an animal that talks, a person who doesn’t die, a stick that heals. A table from Justin Barrett covers all of the bases (see Figure 1).

This table covers the panoply of figures in religions, mythologies, folklores, but also science fiction movies and fantasy novels. A zombie is a person lacking human consciousness (a violation of expectations regarding psychology); a ghost is a person without a body (a violation regarding biology); a talisman is an artifact with magic properties (physics violation); Ents are plants that behave like people (biology and psychology violations); monotheistic gods are often people lacking bodies and with reality-defying powers (psychology, biology, and physics violations). And so on.

A primary postulate for why counterintuitive imagery is so common in the religious imagination is because it is better remembered. But we need not restrict ourselves just to the religious imagination in this regard (Barrett, “Utility” 250). Atran and Norenzayan did experiments where stories with counterintuitive imagery were better remembered after one week (see also Barrett and Nyhof). Perhaps most interesting, they found an ideal ratio of counterintuitive to intuitive imagery (mostly intuitive with some counterintuitive), which accounts for why all or even most religious imagery is not counterintuitive. This is an explanation for its universality – in a tradition lacking writing, imagery that was better remembered would have a Darwinian advantage. And, indeed, such imagery does seem to be universal. Donald Brown lists belief in the supernatural, anthropomorphism, magic (which involves category violations of some sort), and myths all as human universals (139).

This may explain the abundance of spirits, and giants, and witches, and gods and the like – all the mythic figures that populate the religions, folklores and stories the world over, all of which have their roots, if you go back far enough, in the letterless past. But can we say the same about wizards and aliens and all the creations of modern fantasy and science fiction that are solidly within modern times? Clearly memory is no hurdle to the retention of something located conveniently in paperback or blue-ray. Indeed, if we extend our view to incorporate our metaphors (your eyes are like diamonds, a mountain of a man, fast as a cheetah), counterintuitivity pervades all of our narrative, even the most realistic.

This points to a possible need to expand what we mean by the term “supernatural.” Rather than being the domain of magic, mysticism, or the occult, an understanding of our innate folk physics and folk biology lets us understand why exactly we draw a line between natural and supernatural, and that there is nothing inherently religious or magical about things on the other side of that line. As Konika Banerjee notes (Banerjee et al.), in actuality, we likely get the directionality wrong: counterintuitive imagery isn’t religious, there’s just something about it that leads to its overrepresentation in allforms of narrative. The “supernatural” (read: counterintuitive) surrounds us, we just tend to notice only the more extreme examples found in mythology and religion. This meshes quite well with the work of Kelly and Keil that found similar rates of cross-domain transformation in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Grimms’ Fairy Tales.

But if counterintuitive imagery is so ubiquitous, even (especially?) into the modern day where memory is no longer a restricting factor, what can account for its prevalence? Why would Hinduism, Ovid, and comic books all contain similar imagery? Banerjee uses the phrase “inferentially rich,” which may be on to something. If a novel counterintuitive idea breeds new ideas and images, this may make them more attractive. There is perhaps something more creative about them. This fits with one approach to creativity at the cognitive level that assumes creativity to involve the combination of two previously separate ideas in working memory (Vandervert et al.; Fink et al.). Thus, counterintuitive imagery may force us to be creative in reverse by separating the components of a hybrid that we had not encountered. But much more research is required on this specific question.

An Attempt to Test Some Hypotheses

Based on the standard formulations of the role of counterintuitive imagery in religions, I formulated two hypotheses that could be empirically tested. First of all, if memory is truly the main reason for increased counterintuitive imagery, we should find more of it in oral traditions than written traditions. Second, if there is something religious about counterintuitive imagery, we should find more of it in religious texts than non-religious texts. Obviously, counterintuitive imagery exists in both written and secular texts, but there should be some difference in the rates. With these hypotheses in mind, I and a group of undergraduate students began to tabulate rates of counterintuitive imagery. The project is highly labor intensive and so progress is both slow going and narrowly focused. Consequently, conclusions are so far highly tentative and really only serve as means of directing future research. But the data has been interesting, nonetheless (Dolack). To date we have gotten through the Hebrew Bible and the Harry Potter series, which is only a starting point. Obviously, this choice alone is a delimiting factor in the results, but we believe that at the very least we have established that a fuller empirical study along these lines promises to contribute to worthwhile research programs on counterintuitive imagery and narrative.

What we have done is tabulate all of the characters in both works (over 3,500 total) and, using the rubric established by Boyer and Barrett (“Natural Foundations”), marked which ones had counterintuitive elements. Specifically, we tracked whether each character had some additional, unanticipated domain capacity in psychology, biology, or physics, or whether it lacked such a capacity (marked as +psychology, or –physics, for instance). Some simplification was necessary, especially at this stage. Future work could involve the subtlety built into Justin Barrett’s coding system, particularly his distinction between “counterintuitive” and “counterschematic” (Barrett, “Coding”).

Some of our basic results showed that only 8% of characters in the Old Testament had some form of domain violation. However, if we counted not just characters, but how many times the characters were mentioned, it turns out that 33% of character mentions involve a character with a domain violation. This means that counterintuitive figures were much more likely to be mentioned multiple times than “normal” figures. This fits with the predictions of the theory – there is obviously selection pressure for counterintuitiveness in the Bible.

To test another prediction, we tabulated the percentage of character mentions involving a counterintuitive character per book of the Bible. We did percentage and not raw numbers because otherwise larger books such as Genesis would have an unfair advantage. The results look like Figure 2.

Some books have very high numbers because they only have a handful of people, all of whom are prophets, or fall into some other counterintuitive category. The test here was to see if the earlier books of the Bible (the ones more likely to date back to a purely oral tradition) had higher or lower rates of counterintuitive figures. Dating books of the Hebrew Bible is tricky as there are no exact dates to begin with, but things are further complicated by when texts were written down or edited. But using a rough ordering, my team came up with Figure 3, which shows a general decrease from older to newer texts.

The overall decrease in the percentage of domain violations fits with the model’s predictions as well. But what happens when we look at a work of contemporary fantasy? Our prediction based on theory was that rates of counterintuitive imagery would be lower, but our instincts said it would be about the same. It turns out that 45% of the characters in the Harry Potter novels are counterintuitive. That’s far higher than the 8% in the Hebrew Bible. If we look at character mentions, the disparity is much less: 49% compared with The Bible’s 33%. The percentage of mentions jumps much less than with The Bible; a counterintuitive character in Harry Potter is only slightly more likely to be seen more often than a non-counterintuitive character. We suggest this difference is because the initial rate in Harry Potter is so high and because The Bible was winnowed down and changed over centuries.

What conclusions can we draw from this admittedly narrow selection of texts? Based solely on this one example we can say that individual, modern, written works can have as much or even more counterintuitive imagery than religious or oral texts. Indeed, this is another sign of the universality of counterintuitive imagery. It also supplies support for the hypothesis that memorability may not be the only reason for the prevalence of such imagery. Harry Potter is not dependent on long-term memory for its propagation, only its appeal to readers. So perhaps counterintuitive imagery is more engaging (or exciting, or rich), and not merely more unforgettable. These results point more to what work needs to be done than to answers to our original questions.

Future Research

This line of research clearly needs more data from as many different sources as possible. There is no way for two works to give an accurate view of the problem; what we have been able to do is more akin to a pilot study that prepares the way for more systematic work. For starters, we should compare rates of counterintuitive imagery in cross-cultural folklore and mythology to see if there are geographical variations in rates or preferences. (Work already appears to show that counterintuitive imagery is cross-cultural. See Boyer and Ramble, and Barrett et al.) Second, we need more work on counterintuitive imagery in literary texts. What are the factors that affect counterintuitivity – genre? tradition? audience? Do counterintuitive elements appear in our metaphors at the same rate as counterintuitive images appear in folklore? Finding counterintuitive imagery in a broad range of works and types of work would suggest that it is fundamental to our imagination. Lastly, these data can be used to investigate why this type of imagery is so pervasive since it seems that memorability alone cannot be the answer. This could be a consequential undertaking, because any line of investigation that gets to a possible common root of religion and the narrative arts could also shed light on the evolutionary origins of both behaviors. Common ancestors are not just valuable in anthropology and paleontology.

Works Cited

Atran, Scott. “Basic Conceptual Domains.” Mind and Language 4.1–2 (1989): 7–16.

Atran, Scott. In Gods We Trust: The Evolutionary Landscape of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Atran, Scott, and Ara Norenzayan. “Religion’s Evolutionary Landscape: Counterintuition, Commitment, Compassion, Communion.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27.06 (2004): 713–730.

Aubert, M., et al. “Palaeolithic Cave Art in Borneo.” Nature 564.773 (Dec. 2018): 254-257.

Banerjee, Konika, O. S. Haque, and E. S. Spelke. “Melting Lizards and Crying Mailboxes: Children’s Preferential Recall of Minimally Counterintuitive Concepts.” Cognitive Science 37.7 (Sept. 2013): 1251-89.

Barrett, Justin L. “Coding and Quantifying Counterintuitiveness in Religious Concepts: Theoretical and Methodological Reflections.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 20.4 (2008): 308–338.

Barrett, Justin L.“Exploring the Natural Foundations of Religion.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4.1 (Jan. 2000): 29–34.

Barrett, Justin L.“The (Modest) Utility of MCI Theory.” Religion, Brain & Behavior6.3 (July 2016): 249–251.

Barrett, Justin, and Melanie Nyhof. “Spreading Non-Natural Concepts: The Role of Intuitive Conceptual Structures in Memory and Transmission of Cultural Materials.” Journal of Cognition and Culture 1 (Feb. 2001): 69-100.

Boyer, Pascal. “Evolution of the Modern Mind and the Origins of Culture: Religious Concepts as a Limiting Case.” Evolution and the Human Mind: Modularity, Language and Meta-Cognition. Ed. Peter Carruthers and Andrew Chamberlain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, 93–112.

Boyer, Pascal.Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Boyer, Pascal, and Charles Ramble. “Cognitive Templates for Religious Concepts: Cross-Cultural Evidence for Recall of Counter-Intuitive Representations.” Cognitive Science 25.4 (July 2001): 535–64.

Brown, Donald E. Human Universals. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1991.

Burdett, Emily, Justin L. Barrett, and Tenelle Porter. “Counterintuitiveness in Folktales: Finding the Cognitive Optimum.” Journal of Cognition and Culture 9.3 (Oct. 2009): 271–87.

Dolack, Tom. “A Quantitative Approach to Counterintuitive Imagery in the Hebrew Bible and the Harry Potter Novels.” Evolution and Popular Narrative. Ed., Dirk Vanderbeke and Brett Cooke. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Brill Rodopi, 2019, 264-291.

Fink, Andreas, et al. “Stimulating Creativity via the Exposure to Other People’s Ideas.” Human Brain Mapping 33.11 (2012): 2603–2610.

Guthrie, Stewart. Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Hawks, John. “Neanderthal Humanities.” Darwin’s Bridge: Uniting the Humanities and Sciences. Ed. Joseph Carroll, Dan McAdams, and Edward O. Wilson. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016, 89–100.

Henshilwood, Christopher S., Francisco d’Errico, and Ian Watts. “Engraved Ochres from the Middle Stone Age Levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa.” Journal of Human Evolution 57.1 (July 2009): 27–47.

Hoffmann, D. L., et al. “U-Th Dating of Carbonate Crusts Reveals Neandertal Origin of Iberian Cave Art.” Science 359.6378, 23 (2018): 912–915.

Joordens, Josephine C. A., et al. “Homo Erectus at Trinil on Java Used Shells for Tool Production and Engraving.” Nature 518.7538 (2015): 228–31.

Kelly, Michael H., and Frank C. Keil. “The More Things Change…: Metamorphoses and Conceptual Structure.” Cognitive Science 9.4 (1985): 403–416.

Mithen, Steven J. The Prehistory of the Mind: A Search for the Origins of Art, Religion, and Science. London: Thames and Hudson, 1996.

Swan, Thomas, and Jamin Halberstadt. “The Mickey Mouse Problem: Distinguishing Religious and Fictional Counterintuitive Agents.”PLOS ONE 14.8 (Aug. 2019).

Vandervert, Larry R., Paul Schimpf, and Hesheng Liu. “How Working Memory and the Cerebellum Collaborate to Produce Creativity and Innovation.” Creativity Research Journal 19.1 (2007): 1–18.

Particular Works and Literary Universals: As You Like It

Patrick Colm Hogan, University of Connecticut

Particular literary works figure in the study of literary universals principally as data from which researchers may abstract cross-cultural principles. However, the isolation of literary universals may also have consequences for our understanding of individual works. Consider story genre. I have argued that a limited number of such genres recur across a range of unrelated traditions (on the nature of these genres, see “Story”; on the cross-cultural evidence for the genres, see my The Mind and Its Stories and Affective Narratology[1]). These are not the only possible genres. However, their cross-cultural recurrence suggests their cognitive and affective salience and even predominance. For this reason, the cross-cultural genres are often more valuable in categorizing literary works or parts of works than are the historical categories to which works were assigned by their contemporaries. (In a similar way, our diagnostic categories are typically more valuable in categorizing illnesses than are the diagnostic categories to which a person’s illness was assigned by his or her contemporaries.) For example, in How Authors’ Minds Make Stories, I have contended that the cross-cultural genres do a better job of organizing Shakespeare’s plays than the traditional, fourfold scheme of comedies, tragedies, histories, and romances.[2]

In the present essay, I set out to consider a single work—Shakespeare’s As You Like It—in relation to cross-cultural story genres. Though his plays are generally open to categorization in one or another dominant genre, it is well known that Shakespeare mixed genres.[3] In the following pages, I will consider the ways in which different story trajectories in the play may be usefully analyzed as instances of different, cross-cultural genres. This analysis allows us, in turn, to isolate some of the play’s stylistic techniques and thematic concerns more clearly and to explore them more fully.[4]

More exactly, one useful method of exploring Shakespeare’s play begins by isolating the various story sequences–the story of Orlando and Oliver, that of Touchstone and Audry, and so on—then identifies their genres and determines how Shakespeare particularized those genres. Such an analysis suggests conclusions about Shakespeare’s story style and about the thematic resonances of the work, both ethico-political and psychological. However, before treating As You Like It, I should outline the main features of the relevant story genres and some of the key principles used by authors in developing particular literary works.

Cross-Cultural Story Genres, Motifs, and Development Principles

It is important to make three general points about literary universals. First, like linguistic universals, literary universals may be absolute (recurring in all traditions), near absolute, statistical (recurring in a significantly greater percentage of traditions than would be expected by chance), or typological/implicational (recurring in traditions of a specified type). Second, “unrelated” means that the traditions have distinct origins and have not influenced one another extensively. Thus, English and Twentieth-Century Chinese literatures are related; evidence for cross-cultural patterns would have to draw on Chinese and European works prior to the period of modern, European colonialism. Third, universals are not exhaustive. One can tell stories about anything. Stories are not confined to the cross-cultural genres. On the other hand, as already noted, the cross-cultural genres tend to be particularly salient and prominent; traditions appear more likely to differ in recurring patterns of particularization than in the main genres themselves.

The mention of particularization leads us to development principles. In How Authors’ Minds Make Stories, I have argued that the creation of particular stories may be understood in part as the application of development principlesto cross-cultural genre prototypes. These development principles comprise principles governing specification (where abstract elements in the prototype, such as “lovers,” are given particular features), completion (the filling in of ellipses), extension (the combination of different prototypes or motifs), and alteration (deviation from a prototype). Development principles may bear on the story itself (as just indicated) or on aspects of discourse, thus the narrational point of view, the emplotted order of information (e.g., strictly chronological or partially chronological with flashbacks), and so on.

In analyzing As You Like It, I will be concerned with three cross-cultural story genres (romantic, heroic-usurpation, and familial) and one cross-cultural motif (remorse and conversion). In The Mind and Its Stories and Affective Narratology, I have argued that cross-cultural genres prototypically involve one or two protagonists pursuing some goal. The goal is defined by an emotion system or some integration of emotion systems. The cross-cultural elaboration of the story trajectory functions to intensify the outcome emotion. In the full, comic form of each genre, this leads to the apparent loss of the goal in the middle of the story.

The romantic genre develops out of the integration of attachment and sexual desire (as well as the reward system) in romantic love. The romantic story prototype forms around two people falling in love, but finding their union prevented by society (commonly intensified by making the blocking figures loved ones, such as parents). This social interference commonly involves a rival and thus a love triangle, and the apparently permanent separation of the lovers (often through rumors of death). However, in the full, comic version, the lovers are ultimately united and social rifts overcome.

The heroic genre is based on the emotions of pride, shame (thus a violation of pride), and anger (due to shame), bearing on characters and on groups. In its prototypical form, this genre has an individual part and a collective part. The collective part involves a threat to the hero’s in-group (commonly the nation) from some enemy out-group. The individual part prototypically treats the usurpation of a leader’s rightful position, a usurpation often emotionally intensified by making the usurper an attachment object, such as a sibling. In the comic version, the story is commonly resolved through combat in which the usurper is defeated (often killed) and the legitimate authority reinstated.

The familial genre is based on attachment feelings. It concerns the separation and reunion of family members. The separation may be intentional on the part of the parents or children, and the reasons for the separation vary. The reunion is often less joyous than one might anticipate, given that the parents’ age may imply that this reunion will soon be cut short by their death. It may also involve feelings of guilt and remorse for the initial separation.

Finally, in The Mind and Its Stories, I distinguish story genres from story motifs. Story genres are derived from emotion-defined goal pursuit, as just explained. Motifs, in contrast, are types of event sequence that may be incorporated into various genres as they are not linked intrinsically with any genre-defining goal.[5] Like genres, some particular motifs are cross-cultural, while others are not. For example, the quest is often cited as a cross-cultural literary structure.[6] In my account, a quest does not define a genre, but a cross-cultural motif that may be incorporated into any genre. For example, the usurped hero or the struggling lover or the abandoned child—that is, types of character from the universal genres (heroic, romantic, and familial, respectively)–may undertake a quest in the service of regaining his or her kingdom, being joined in marriage with his or her beloved, or being reunited with his or her family. (A motif may, of course, be elaborated into a full story. But that is only because anything may be elaborated into a full story. That does not make everything into a cross-cultural genre.) In As You Like It, the motif I have in mind is, roughly, that of remorse leading to self-reformation or “conversion” in a broad sense. This motif often appears at the conclusion of heroic works in what I have called the “epilogue of suffering” (see chapter four of The Mind); it leads to the hero’s abandonment of the very goals he or she had striven for (and even achieved) in the rest of the story.

The Stories of As You Like It

The first scene of the play introduces us to the story of Orlando and Oliver, a reduced or deflated version of the heroic usurpation story. It is “reduced” in the sense that it concerns family relations rather than a nation. However, it involves the same denial of social position and even a murder (or assassination) plot. This scaling down of the heroic usurpation is facilitated by the fact that the national usurpation story is often intensified by being familial in the sense of involving betrayal of the hero by a family member. For simplicity (and as a sort of homage to Russian formalist practices), I will refer to the narrative trajectories through abbreviations. This first heroic usurpation story is HU1 (“heroic usurpation 1”).

One stylistic feature of Shakespeare’s writing is his tendency to develop parallel story sequences. Sometimes he invents them; sometimes he draws them from his sources (which he presumably found appealing in part due to the parallel stories). He frequently treats these parallel stories in contiguous scenes. In keeping with this, I.ii introduces the backstory to a more standard heroic usurpation story (HU2), also one involving brothers, that of Dukes Frederick and Senior. In addition, it introduces our first family separation story (FS1), that of Rosalind and Duke Senior, which results from HU2. This scene continues HU1 as well, by thwarting Oliver’s plot to have Orlando killed. The combat between Oliver and the wrestler is drawn from the source, with the important difference that the latter is (presumably) not killed.[7] This allows the possibility that no irreversible damage is done by the main characters in the course of the play (a point that bears on Shakespeare’s development of heroic stories, as we will see). This wrestling match is not only part of HU1, but also part of the first romantic story of the play (R1)—that of Rosalind and Orlando. In the love story, it represents the common device of a contest in which the lover impresses the beloved with his manly skills. Shakespeare not only parallels, but also frequently integrates his separate story sequences, as in this crossing of HU1 with R1. We find another case of this sort when Duke Frederick suggests that Orlando’s father sided with Duke Senior in Duke Frederick’s usurpation. This intertwining of HU1 and HU2 will be extended later in the play.

The third scene allows Rosalind and Celia to elaborate on Rosalind’s feelings for Orlando (thus R1). It also introduces the exile of Rosalind. This initially raises the possibility of Rosalind and Celia being separated. But Celia protests that “thou and I am one” and thus should not be “sund’red” (I.iii.95, 96). They therefore determine to go together into exile. Though little developed in what follows, this does introduce a second familial separation sequence (FS2), that between Celia and Duke Frederick.

Having introduced the exile of Rosalind and Celia, Shakespeare turns in II.i to the prior exiles of HU2—Duke Senior and his companions. An interesting element of this scene involves Jaques’s (reported) objection to hunting and his “weeping” over a deer that they have killed (II.i.65). Jaques “swears” that the hunters “do more usurp” than Duke Frederick (II.i.27). Here, Shakespeare draws on the model of the heroic prototype to consider hunting and tacitly analogizes Jaques’s grief (see II.i.26) to the remorse felt by the heroes in the heroic epilogue. This is then the first suggestion of the conversion motif, CM1. The motif will recur in the stories of Oliver and Frederick. It is an instance of Shakespeare’s multiplication of parallel story sequences and is not found in the source. As we will see, unlike the conversions of Oliver and Frederick, that of Jaques appears to concern promiscuity or hedonism, rather than usurpation; however, in this scene, Shakespeare connects Jaques’s conversion with usurpation in a way that appears very much like remorse.

The second scene of act two fundamentally serves to inform us that Rosalind and Celia have followed through on their plans to leave. It thereby establishes the separation of Duke Frederick and Celia, FS2. In his usual, tidy manner, Shakespeare moves in II.iii to the exile of Orlando, when faced with another assassination plot from his usurping brother. Finally, in II.iv, we see Rosalind, Celia, and Touchstone in the forest, simply shifting the narrational point of view regarding HU2, FS1, and FS2.

II.v serves to develop Jaques’s melancholy, which is consistent with his motivic role relating to remorse and conversion. II.vi and II.vii principally elaborate on the condition of the exiles of HU2. II.vii further integrates the story sequences of HU1 and HU2 by having the exiles—Orlando, Duke Senior, and so on—meet. This scene also includes some slight hints of Jaques’s backstory, that he lived riotously before he became somber and reflective (see II.vii.62-69). This too points toward a (subdued) motif of remorse and conversion (CM1), already hinted at in the report of Jaques’s grief over the deer (II.i.65).

The third act begins with a further integration of the two usurpation sequences, HU1 and HU2, as Frederick threatens Oliver with dispossession if he does not capture or kill Orlando. In terms of emplotment, this revives the suspense of HU1 as it poses a new threat to Orlando, whom we might otherwise have assumed to be out of danger. The second scene involves many elements, principally developing character, provoking mirth, and serving other purposes. For our interests, the second scene most importantly sets up the relation between Oliver and Ganymede. This sequence draws on a motif found in some romantic stories (such as Shakespeare’s own Cymbeline), where one of the lovers determines to test the sincerity and durability of the other’s affection, though it recasts that motif as a sort of open joke.[8] At times, however, the joke seems to shift into a nearly real seduction of the lover being tested.[9]

By the beginning of the fourth act, the relation between Orlando and Rosalind—in the guise of Ganymede–almost appears to constitute another story of romantic love (R2). Of course, this is not a different love story for Rosalind, who is continuously enamored of Orlando. The question concerns just what Orlando’s feelings might be for the person he identifies as Ganymede, not Rosalind. This is particularly significant as the relation between these two is developed somewhat differently in the source. At least in my reading, Lodge’s Orlando (there called “Rosader”) is more clearly playacting. Indeed, after their first recitation of poetry in the assumed roles, Rosader asserts the falsity of their pretense. Shakespeare makes their connection—a matter of wooing “every day” in her “cote” (III.ii.417)–more evidently romantic and thus ambiguous on Orlando’s side. For example, Orlando’s phrase, “fair youth” (III.ii.377) suggests an appreciation of Ganymede’s physical beauty, in contrast with Rosader’s “gentle swain” (Lodge). Orlando speaks directly to Rosalind/Ganymede of kissing her/him rather than merely talking (IV.i.68), whereas Rosader’s only reference to kissing occurs in a poem and refers (somewhat confusingly) to “Love” kissing “roses” (Lodge). In connection with this, there seems to be some bawdy ambiguity in Orlando’s plea to “have me” (IV.i.111) following Ganymede’s “more coming-on disposition” (IV.i.106-107), and his subsequent urging of Celia/Aliena, “Pray thee marry us” (IV.i.120). In contrast, when Lodge’s Aliena suggests a mock marriage, Rosader agrees and “laugh[s]”; moreover, the entire business is characterized as a “jesting match,” again stressing the distance between the people (Rosader and Ganymede) and the roles they are playing (Rosader and Rosalynde).

Punctuating the development of R2 (Orlando and Ganymede), Shakespeare indulges his penchant for parallel story sequences. One of these is drawn from the source. In III.v, we find the love triangle of Silvius, Phebe, and Ganymede (R3). Before this, in III.iii, we find the romantic story of Touchstone and Audry (R4), added by Shakespeare. This is a very minimal story in that the obstacles to their union seem to be largely a matter of getting the marriage ceremony set up. Though parallel with the story of Orlando and Rosalind (R1), both these stories are deromanticized. Phebe seems to have no interest in Silvius whatsoever. In the end, she marries him because she lost a bet. As to Touchstone and Audry, the former makes a mockery of the entire process from start to finish. This is not to say that their marriage is doomed. Touchstone is certainly sharp-tongued, but he seems fundamentally benevolent. Mockery is his profession; as he himself says, “we that have good wits have much to answer for. We must be flouting; we cannot hold” (V.i.11-12). The audience should probably not take that mockery too seriously with respect to his marriage. Nonetheless, we might infer from these cases that the romanticization of love may be mistaken—even in the case of Rosalind and Orlando (as well as Celia and Oliver, to which we will turn shortly). The idea is consistent with some suggestions of the larger organization in story trajectories, as we will see.That deromanticization may be suggested also by the odd scene, IV.ii, in which Jaques makes jokes about cuckoldry and horns—a tiresomely repetitive form of humor that Shakespeare incomprehensibly found irresistible.

The third scene of the fourth act resolves HU1. This occurs when Oliver’s life is endangered. Orlando is tempted by “revenge” (IV.iii.129), thus the violent response to usurpation, the usual development of the heroic plot. But he foregoes this response, saving his brother’s life. This leads to Oliver’s “conversion” (IV.iii.137). Thus, we have a second instance of the conversion motif (CM2), in this case operating not as an epilogue for the heroic story, but as the resolution to that story itself, a resolution that substitutes for the violence and destruction that would have given rise to the epilogue’s remorse. In How Authors’ Minds Make Stories, I argued that Shakespeare’s use of the heroic structure may allow a genuinely comic conclusion insofar as no irreversible loss—most obviously, death–has occurred. His ideal outcome appears to be a matter of forgiveness and reconciliation, not violent retribution. (As Oliver puts it, “kindness” is “ever nobler than revenge” [IV.iii.129].) In this case, the main events and possible motives or outcomes (e.g., Rosader/Orlando taking “revenge”) are largely found in the source for the play. Moreover, in Lodge, Oliver (there called “Saladyne”) does experience remorse and a sort of conversion (cf. his resolution to do “penance” and be a pilgrim to “the Holy Land” [Lodge]). This does not make the point any less Shakespearean, since there must be aspects of a source work that drew Shakespeare to it initially. Moreover, in Shakespeare’s play, the motif recurs not only in HU1, but more importantly in HU2, the other heroic usurpation sequence, as we will see. Here, as elsewhere, the enhanced story symmetry or multiplication of story parallels is characteristic of Shakespeare, no less than the thematic preference.

This scene also introduces us to yet another love story (R5). This one is between Oliver and Celia. Moreover, in the typical, Shakespearean fashion, it is integrated with HU1, as it is allowed by the resolution of the brother conflict in that story.

The first scene of the final act develops the Touchstone-Audry love story (R4) by introducing and summarily dismissing a rival. The second scene elaborates on the Oliver-Celia romance (R5). That scene ends with a sort of cliffhanger bearing on the possible marriages in the stories R1 (Rosalind-Orlando), R3 (Phebe-Silvius), and R5 (Celia-Oliver). The following scene simply extends this cliffhanger to R4 (Touchstone-Audry).

The final scene resolves most of the story sequences in short order. Rosalind reveals her identity, which leads to her official reunion with her father and the resolution of the Silvius-Ganymede competition. This, in turn, enables the marriage of Silvius and Phebe, who are wed at the same time as Orlando and Rosalind, Touchstone and Audry, and Celia and Oliver. This resolves FS1, R3, R1, R4, and R5 simultaneously, leaving only HU2 (Duke Senior’s usurpation), FS2 (the separation of Celia and her father), and perhaps R2 (the [imaginary?] relation between Orlando and Ganymede).

Before going on to these, I should remark briefly on one peculiar aspect of the resolutions we have already treated. In Shakespeare’s play, Rosalind encounters her father well before she reveals herself to him (see III.iv.32-36). It is not at all clear why she did not reveal herself to her father when they first met.[10] The male disguise was supposedly for her and Celia’s protection (I.ii.106-120), though they did have a male companion in the form of Touchstone. But this is clearly unnecessary when her father and his retinue are present. The most obvious explanation has to do with her testing of Orlando. There may, however, be other possibilities, suggested by unresolved parts of the work. (We will return to this point.)

The Frederick-Senior usurpation story (HU2) is resolved in a striking departure from the source text. Specifically, Lodge presents us with a typical heroic resolution in which combat leads to the death of the usurper. But, in Shakespeare, the usurper is “converted” (V.iv.161) to a religious life. He abandons the world and returns the kingdom to the legitimate leader, Duke Senior. This is a third instance of the motif of conversion (CM3). Like the story of Oliver, it recalls the heroic epilogue, but in fact replaces the heroic ending, and thus avoids the violence that entails a remorseful epilogue. Moreover, in keeping with CM1, Jaques leaves the rejoicing society to join the converted Duke Frederick. Thus, two of the three “converts” (Frederick and Jaques) retreat from the world into spiritual pursuits. Indeed, the third convert, Oliver, though now married, has also determined to abandon wealth and worldly things to live a pastoral life with Celia (V.ii.12), aptly-named for Heaven.[11] These points are consistent with the generally critical attitude Shakespeare took toward heroic violence.[12] They suggest a thematic repudiation of revenge (by the usurped heroes) and an advocacy of moral self-examination (by the usurping villains). In terms of emotion, love, compassion, and remorse seem to be prized in these stories (HU1 and HU2), not the usual heroic sentiments of anger and pride. Indeed, in both cases, the resolution is more familial than heroic, as the alienated brothers are directly or indirectly reconciled.[13]

On the other hand, Duke Frederick does not rejoin the group and this reminds us that the second family separation story (FS2)—that of Celia and her father—remains unresolved. This may be merely an oversight on Shakespeare’s part. But I will conclude by considering another possibility which connects this unresolved separation with other peculiarities of these stories—the apparent romance of Orlando and Ganymede (R2), the delay of Rosalind in revealing her identity, and the emotionally unsatisfactory quality of the Silvius-Phebe resolution.

Specifically, Celia chooses to be separated from her father in order not to be “sund’red” from her “sweet girl,” Rosalind (I.iii.96), as “thou and I am one” (I.iii.95).[14] Removed from the identity and situation of the speakers, such an appeal would most obviously be taken to express romantic love. Hyperbole of this sort may of course found in friendship. In consequence, I do not wish to make too much of it on its own. But, in relation to the other unexplained or unresolved story sequence in the play—the hint of homoerotic feelings on the part of Orlando for Ganymede–it would appear reasonable to think of it as involving at least a suggestion of romance.[15] In this case, Rosalind would be the forbidden beloved; the separation of Rosalind and Celia would represent the separation of the lovers, and so on. Construed in this way, the exile of Celia is not most importantly part of a familial story, but of a semi-concealed romantic story (R6)—indeed, a romantic story that is relatively prototypical. Of course, in romantic works, parents and children are often reconciled eventually. The possibility of such a reconciliation remains open in this case, particularly given that both Celia and her father appear to be remaining in the forest. However, such a reunion is not so important to the romantic story as it would be to a family separation story; thus, its explicit articulation is less necessary.

As to the Silvius/Phebe/Ganymede story (R3), I suspect that most recipients of the play—audience members or readers–would agree that it is emotionally unresolved (even though we are given a narrative conclusion). There is, indeed, something almost distressing about Silvius and Phebe marrying for no apparent reason other than Phebe losing a wager. The future is hardly promising for either the husband or the wife, given this start to their union. One way of reading their wedding is not as a comic resolution of a Silvius/Phebe love story (where Ganymede is the rival), but as the tragic conclusion of a Phebe/Ganymede love story (where Silvius is the rival), thus R7. Moreover, it does not take a great deal of hermeneutic subtlety to see homoerotic elements here. Phebe’s radical change from a votary of Diana to one of Venus may have to do with the appeal of Ganymede’s presumably feminine features.[16]

Understood thus, the overall pattern of story resolution and non-resolution in the play might be taken to suggest something along the following lines. Orlando and Celia have both heterosexual and same-sex romantic feelings, represented in the hazy, uncertain R2 and R6. The heterosexual feelings (R1 and R5) are clear and explicit. The same-sex feelings, however, are unclear—suggested, but obscurely. It is precisely these implicit, indirectly acknowledged feelings that are sustained, in their ambiguous state, by the preservation of Rosalind’s disguise, itself made possible by her unexplained delay in revealing her identity to her father. It is also precisely these same-sex trajectories that remain unresolved, perhaps because they were unresolvable—either for social reasons or simply because some of our choices in life preclude the pursuit of other interests, or both.[17] A similar pattern is to be found in R3 and R7, the stories of Silvius, Phebe, and Ganymede/Rosalind. The difference here is that it is never clear Phebe has heterosexual feelings at all; related to this, the heterosexual story sequence (R3), though superficially resolved, is unsatisfying. It is resolved formally–in terms of what happens in the story, including Phebe’s statement about a (very speedy) change in her “fancy” (V.iv.150)[18]—but it is not really resolved emotionally, at least for any audience member who reflects on the marriage.

A Note on Future Research

A great deal of literary study involves the careful analysis or interpretation of individual works. Research on literary universals necessarily considers broad patterns beyond individual works. However, this does not mean that universals are irrelevant to particularistic analysis or interpretation. There is clearly a great deal of scope for future treatment of universal story structures and motifs in individual works. In addition, while focusing on story—thus, the actions and events that constitute “what happens” in As You Like It–I set aside the “discourse” aspects of the work, which is to say, the plot selection (what is presented from the story and when it is presented) and the manner of presentation (e.g., depicted onstage or reported by a character). Research on cross-cultural aspects of discourse too should prove a fruitful area for articulating general principles and for analyzing particular works.

Conclusion

We began with the question of to what extent the study of universals might contribute to our understanding of individual works in their particularity. I focused on story universals—genres and motifs—which allow us to isolate particular story trajectories and to consider the ways in which such trajectories repeat, specify, complete, integrate, or alter universals. Considering As You Like It in these terms, and in relation to Shakespeare’s source for the play, we were able to see some patterns in Shakespeare’s story style as well as some thematic concerns that may have been less clear, or even obscure, otherwise.

The stylistic patterns include the multiplication of parallel story sequences, sometimes with a systematic alteration, such as heavily ironic deromanticization, as in the Touchstone-Audry love story. They also include the causal intersection of distinct story lines. The multiplication may be an instance of a more abstract and universal stylistic technique of symmetry enhancement, which may apply not only to sequences of events, but to scenes, the structure of dramatic acts, the generation of characters, or such verbal practices as parallel phrasing.

The thematic concerns include Shakespeare’s preference for repentance and examination of conscience, or “conversion,” over revenge and violence—or, alternatively, his preference for familial reconciliation rather than heroic victory. Perhaps more significantly, somewhat unexpected patterns in the resolution and non-resolution of story sequences may suggest a subdued, partially denied concern with the place of same-sex romantic love in the lives of individuals and in the practices and possibilities offered by society.[19] In short, the preceding analysis suggests that the study of universals, though by its nature general, can and does have consequences for our understanding of particularity. That particularity includes style and theme. It also includes what some psychoanalytically-influenced critics refer to as “symptomatic” elements, concerns that haunt an author, but that he or she has not been able to work through in a systematic and clarifying manner, either for others or for himself or herself.

But that is not all. This examination of As You Like It suggests more general, theoretical ideas as well. Specifically, I take the general structure of the universal story prototypes to tell us something about the ways in which our emotions systems and our processes of simulation (or imagination) operate.[20] In its complex patterns of resolved and unresolved story sequences, As You Like Itindicates some further points about these systems and processes. Specifically, the preceding analysis suggests that we all are regularly engaged in multiple, simultaneous or alternating forms of simulation or imagination. These forms of simulation partially overlap, but also diverge from one another in some respects. Thus, Orlando has complex and various imaginations of Rosalind (whom he has apparently seen only briefly and in the past); these partially converge with his simulations of the features and behavior of Ganymede, as well as his possible interaction with Ganymede. (The same general points hold for other characters as well.)

These various simulations are necessarily interwoven with emotion, including attachment feelings and sexual desire. That interweaving is inevitable because simulation is motivated and emotion systems provide us with motives for both action and thought. The variability of our simulations is in part cognitive, but in part emotive, suggesting that we think of various people in often contradictory ways and emotionally respond to them in often ambivalent ways. Indeed, in some degree, we may respond to a given person as masculine in one context and as feminine in another context; perhaps there is even a sense in which we may sometimes tacitly respond to someone as alternatively male and female (not just masculine and feminine), even if we would never self-consciously affirm such variability.

Finally, some of these simulated trajectories (or imagined stories) may be resolved, while others are not open to resolution. That irresolvablility is sometimes social, as when same-sex union is not accepted. But it is sometimes personal or psychological, in the sense that one sometimes cannot in practice satisfy all one’s emotion systems and simulations. For example, Orlando cannot be united with both Ganymede and Rosalind; similarly, Phebe cannot have the socially acceptable union with Ganymede along with the socially unacceptable union with Rosalind. In a sense, then, none of these stories is fully resolved. But Orlando seems pretty well satisfied with Rosalind alone, thus giving his story a high degree of resolution. The situation is very different with Phebe.[21]

Works Cited

Booker, Christopher. The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. New York: Bloomsbury, 2005.

Danson, Lawrence. “The Shakespeare Remix: Romance, Tragicomedy, and Shakespeare’s ‘Distinct Kind.’” In Guneratne, 101-118.

de Grazia, Margreta and Stanley Wells, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001.

DiGangi, Mario. “Queering the Shakespearean Family.” Shakespeare Quarterly 47.3 (1996): 269-290.

Gilman, Albert, ed. As You Like It. New York: New American Library, 1986.

Guneratne, Anthony, ed. Shakespeare and Genre: From Early Modern Inheritances to Postmodern Legacies. New York: Palgrave, 2012.

Hogan, Patrick Colm. Affective Narratology: The Emotional Structure of Stories. Lincoln, NE: U of Nebraska P, 2011.

Hogan, Patrick Colm. How Authors’ Minds Make Stories. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013.

Hogan, Patrick Colm.The Mind and Its Stories: Narrative Universals and Human Emotion. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003.

Hogan, Patrick Colm. “Story.” The Literary Universals Project(2016), https://literary-universals.uconn.edu/2016/11/20/story/.

Hope, Jonathan and Michael Witmore. “The Hundredth Psalm to the Tune of ‘Green Sleeves’: Digital Approaches to Shakespeare’s Language of Genre.” Shakespeare Quarterly 61 (2010): 357-390.

Lodge, Thomas. Rosalynde or, Euphues’ Golden Legacy. Ed. Edward Baldwin. Boston: Ginn, 1910. (Unpaginated Kindle edition.)

Marcus, Leah. “Anti-Conquest and As You Like It.” Shakespeare Studies 42 (2014): 170-195.

McEvoy, Sean.Shakespeare: The Basics. 3rded. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Nardizzi, Vin. “Shakespeare’s Queer Pastoral Ecology: Alienation around Arden.” ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 23.3 (2016): 564–582.

Neely, Carol Thomas. Distracted Subjects: Madness and Gender in Shakespeare and Early Modern Culture. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 2004.

Segal, Janna. “‘And Browner Than Her Brother’: ‘Misprized’ Celia’s Racial Identity and Transversality in As You Like It.” Shakespeare 4.1 (2008): 1-21.

Snyder, Susan. “The Genres of Shakespeare’s Plays.” In de Grazia and Wells, 83-97.

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It. In Gilman, 35-140.

Traub, Valerie. “Gender and Sexuality in Shakespeare.” In de Grazia and Wells, 129-146.

Wells, Stanley. Shakespeare, Sex, and Love. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010.

Notes

[1] The latter book also includes some (admittedly brief) references to other work in narrative theory (Greimas, Propp, Genette, and others) in relation to the study of emotion and story universals.

[2] For a clarifying, historical account of the traditional genre classification, see Snyder.

[3] Danson goes so far as to say that “the mixed mode is the Shakespearean default mode” (102).One referee for this essay suggested that the traditional classification has perhaps been supported by the statistical analyses of Hope and Witmore. Since this essay is not about the classification scheme for Shakespeare’s plays (being an interpretive analysis of one play), I cannot treat the issue at length here. However, it is worth making three points. First, my claim here is about story structures, specifically that the best way to categorize the story structure of the plays is by reference to the cross-cultural genres. There could of course be other patterns to the plays, depending on the period when they were written, the sceneswhere they are located, or other variables. Second, Hope and Witmore do not in fact find that stylistic features perfectly align with traditional genres. For example, they find “the early history plays massing in one part of the diagram” and “the later history plays, along with some of the tragedies, clustering in another” (390). Finally, even Hope and Witmore findapparent anomalies. For example, Othello clusters with comedies. This is, of course,not because it has a happy ending or makes us laugh. It is, however, related to the fact that most of the works traditionally categorized as comedies are at least in part romantic works (in the cross-cultural scheme)—and so is Othello. In this respect, then, the cross-cultural scheme may fit even Hope and Witmore’s analysis better than the traditional categories that Hope and Witmore presuppose.

[4] By “theme,” I mean implications of the play that are designed to systematically affect the audience’s thought about or response to the real world, the world outside the theater—for example, their judgments about political events. However, by “designed,” I do not mean that the author has self-consciously articulated a thematic concern to himself or herself. Rather, I take it that authors have some sense of whether a particular version of the work is “right,” thus whether it seems likely to produce the (implicitly and often vaguely) desired effects. But the author need not be able to articulate those effects, and may even be mistaken if he or she undertakes to do so. Theme is that part of the desired effects that bears systematically on the audience’s thought about or response to the real world.

[5] One referee worried that my “approach” to motifs differs from that in folklore studies and that I should make this clear. In fact, I would not say that I am treating the same category of object as folklorists, but adopting a different theory. Rather, I am simply using the word “motif” in this particular manner. It is true that my usage is related to my theory of narrative universals (e.g., the motif of the quest is bound up with my account of how space is organized in stories). But the fact that I am using the same term as another writer does not mean that we are talking about the same object. Indeed, that is the point of defining how I use the term, “motif.”

[6] See, for example, chapter four of Booker.

[7] For the most part, the similarities and differences between Shakespeare’s play and Lodge’s work are not consequential for the main purpose of the present essay. The study of universals is or not significant for our interpretation and analysis of individual works—either Shakespeare’s or Lodge’s—independent of whether a particular event is or is not shared by the two of those works. After all, a particular event in Shakespeare’s play is there and bears on interpreting the play, whether Shakespeare got the idea for it from Lodge, some biographical experiences, a free associative process, or something else. On the other hand, the relation between Shakespeare’s and Lodge’s works is important for other considerations, such as claims about Shakespeare’s style or about distinctive features of either work.

[8] The relevance of this motif is perhaps more evident in the source, where Ganymede expresses doubt about whether Rosader/Orlando is “deeply enamoured” of Rosalynde (Lodge), and urges him to turn his attention toward Alinda/Celia instead.

[9] The homoerotic quality of this relation has, of course, been developed by directors and analyzed by critics. For an account of a particularly influential staging of the play, see McEvoy (78-82). As to critics, Wells for example summarizes a common view, writing that “Shakespeare shows us Orlando becoming confused between desire for an imaginary Rosalind and for the boy Ganymede whom the real Rosalind impersonates. It is an ambivalence that would have been enhanced when the real Rosalind was played by a boy, and that would have been signaled and emphasized by the use of the name ‘Ganymede,’ a common term for a man’s young male sexual partner” (106-107). However, as far as I am aware, such analysis has not been developed in relation to prototypical story sequences and their associated expectations. Indeed, the theoretical context for such readings has been very different, as suggested by Segal’s brief summary statement that “As You Like It has become a centrepiece in feminist and/or queer discussions concerning early modern English gender and sexual prescriptions and the theatre’s role in contesting or reconsolidating a patriarchal and/or heteronormative social structure” (1). To some extent, the present reading contests such analyses, in that it does not construe the thematic or emotional points at issue in the same terms; however, I take it that the present analysis is more often complementary to such feminist and queer interpretations.

[10] In Lodge, there is a problem also, though it is slightly attenuated. Upon meeting her father, Rosalynde soon reveals herself. But it is not clear why she does not seek to meet him earlier, since she learns of his whereabouts from Rosader/Orlando, who explains that he is living in the company of “the unfortunate Gerismond [Senior]” (Lodge).

[11] Jay Farness pointed out to me that there is some ambiguity as to whether or not Oliver will follow through on this resolution in the changed circumstances of the ending. Jaques does suggest that Oliver will be returning to his lands (V.iv.189). But the counter-argument here is that Jaques has no reason to know about Oliver’s intentions. Moreover, Oliver had said that he was handing over the family estate to Orlando; this indicates that he was opting for the pastoral life even if he could return to the estate (V.ii.10-12), in which case the changed circumstances should not matter.

[12] With the exception of Henry V; see Hogan, How 56-58.

[13] Other critics have noted that there is something un-heroic and un-military about Shakespeare’s play. For example, Marcus interprets the play as involving a critique of colonialism, with Jaques as a sort of repudiated colonial figure. I obviously believe Marcus was onto something. However, by relating the story sequences of the play to cross-cultural prototypes, I have come to a much different interpretation of these un-heroic aspects of the play, and of Jaques’s retreat at the end. I take it that my interpretation is incompatible with Marcus’s view of Jaques, but it is at least potentially compatible with her more significant claims about anti-colonialism.

[14] This echoes Celia’s/Alinda’s even more suggestive assertion in the source that the two share “a secret love” and that they “have two bodies and one soul” (Lodge).

[15] This has been stressed by some recent critics, though (again) in a different theoretical context, which leads to different development of the shared idea (see, for example, Nardizzi).

[16] This is clearer in Lodge, through Phoebe’s stress on Ganymede’s “beauty.”

[17] Again, prior critics have recognized the homoerotic elements in the play; however, they have not analyzed these elements in relation to the genre of particular story sequences. In part for this reason, and in part because their theoretical presuppositions are very different from my own, their conclusions about these elements is often quite different from mine. For example, in a pathbreaking essay, DiGangi maintains that “the marriages succeed to the extent that premarital female homoerotic desire and post-marital male homoerotic desire have been successfully banished” (271). My view is rather that most of the characters in the play have some degree of bisexual desire, manifest in different romantic storylines, more or less following a romantic prototype; however, social constraints and the limitations imposed by life choices prevent the homoerotic storylines from reaching a resolution. This leads to unresolved heteroerotic storylines only in the case of Phebe, for in her case the heteroerotic storyline is not reciprocal; again, she has been married off to the undesired rival, not the beloved. Despite these and other differences, however, I believe that the present reading is more complementary to DiGangi’s than contradictory of it. Certainly, his highly informative treatment of the literary and social history that contextualize Shakespeare’s play adds greatly to our understanding of same-sex desire in the play, and it does so in a way that would not really be possible for an interpretation based solely on literary universals. On the other hand, the point of the present essay is not that interpretation based on literary universals is sufficient or complete, merely that it provides insights not readily available otherwise.

[18] Some critics have seen such swift alterations as part of the play’s “destabilizing” of hegemonic norms of gender and sexuality. Though I am very skeptical of such a conclusion on this particular point, it is clear that the play can serve to challenge some rigid assumptions about gender and sexuality (for a nuanced discussion of this topic, see chapter four of Neely).

[19] Of course, this analysis in terms of particular, same-sex, romantic storylines can be developed only if one first recognizes that “homoerotic desire is evinced in Shakespeare’s plays” (Traub 142). But this initial recognition seems to be more a matter of not suppressing relatively clear indications, rather than one of particular hermeneutic insight.

[20] I have treated these topics at length in The Mindand Howrespectively.

[21] An earlier version of this essay was part of the seminar on As You Like It seminar of the 2019 annual convention of the Shakespeare Association of America. I am grateful to the seminar participants for their comments, questions, and suggestions.

Phonetic Symbolism: Double-Edgedness and Aspect-Switching

Reuven Tsur, Tel Aviv University and Chen Gafni, Bar-Ilan University

This article proposes a structuralist-cognitive approach to phonetic symbolism that conceives of it as of a flexible process of feature abstraction, combination, and comparison.[1] It is opposed to an approach that treats phonetic symbolism as “fixed relationships” between sound and meaning. We conceive of speech sounds as of bundles of acoustic, articulatory and phonological features that may generate a wide range of, sometimes conflicting, perceptual qualities. Different relevant qualities of a given speech sound are selected by the meaning across lexical items and poetic contexts. Importantly, speech sounds can suggest only elementary percepts, not complex meanings or emotions. Associations of speech sounds with specific meanings are achieved by extraction of abstract features from the speech sounds. These features, in turn, can be combined and contrasted with abstract features extracted from other sensory and mental objects (e.g. images, emotions). The potential of speech sounds to generate multiple perceptual qualities is termed double-edgedness, and we assume that the cognitive mechanism allowing us to attend to various aspects of the same speech sound is Wittgenstein’s aspect-switching.

We discuss examples of phonetic symbolism in poetry, lexical items across languages, and laboratory experiments, and show how they can be accounted for in a unified way by our cognitive theory. Moreover, our theory can accommodate conflicting findings reported in the literature, e.g. regarding the emotional qualities associated with plosive and nasal consonants. Crucially, the theory is scalable and can account for general trends in poetry and lexical semantics, as well as more local poetic effects. Thus, the proposed theory can generate predictions that are testable both in laboratory experiments and in formal literary analysis.

Introduction

Many current studies in phonetic symbolism begin with a list of recent works on phonetic iconicity, that allegedly challenge de Saussure’s arbitrariness conception of the linguistic sign, followed by a series of experiments that establish a statistical relationship between phonemes (or groups of phonemes) and meanings or emotional qualities. In these works iconicity is assumed to be somehow given; very few of them go systematically into the structural relationship between the phonemes and the meaning or emotional qualities. In this practice, we strongly disagree with them on three issues.

First, we argue that literary phonetic symbolism does not challenge the arbitrariness hypothesis, but rather confirms it: sound-symbolic effects are attributed to verbal constructs after the event. Second, we believe that research based on stimulus–response questionnaires is, in itself, unsatisfactory. A cognitive approach should include a hypothesis, based on cognitive and linguistic research, to account for the structures in our mind that mediate between stimulus and response. Third, many of those stimulus–response studies take it for granted that rigorous quantitative analysis is the only valid way to evaluate empirical data. Furthermore, many such studies are interested only in global, gross effects (e.g. whether the frequencies of certain phoneme groups alone can account for the perception of poems as ‘happy’ or ‘sad’). We have pointed out a welter of incongruent statistical results in phonetic symbolism (Tsur & Gafni, forthcoming). The confusion in this domain originates in the neglect of a systematic theoretical framework. This neglect may manifest, among other things, in failure to treat sound–meaning relationships at a sufficiently fine-grained level, insufficient awareness of the complexity of the subject matter, as well as confusion whether sound-symbolic effects are motivated by acoustic, articulatory or phonological aspects of speech sounds.

The aim of this article is to present a comprehensive theoretical and analytic approach to sound–emotion relationships in poetry. At the basis of our investigation are earlier works by Benjamin Hrushovski (“interaction view”; 1980) and Iván Fónagy (“Communication in Poetry”; 1961), followed by Tsur’s work in the nineteen-eighties. Both Hrushovski and Fónagy revealed, by different methods, important relationships between speech sounds and their perceived effects.

In a structuralist theoretical discussion of sound–meaning relationships in poetry, Hrushovski explored the complexity of the subject, pointing out sources of complexity, of which we shall discuss here only one: what we call the “double-edgedness” of sibilants: that in some contexts they may express noise of varying intensity, in some — a hushing quality. Alternatively, they may be “neutral”, not related to “meaning” or attitudes at all. Consider the following excerpts:

- When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste

(Shakespeare, “Sonnet 30”)

- And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me — filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating,

“‘Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door —

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door; —

This it is and nothing more.”

(E.A. Poe, “The Raven”)

- [ . . ] the deep sea swell

[ .. .] A current under sea

Picked his bones in whispers,

(T. S. Eliot, “The Wasteland,” IV)

- And swell renews the salt savour of the sandy earth

(T. S. Eliot, “Ash Wednesday”)

In Excerpt 1, the sibilants have a hushing quality; in Excerpt 2, they imitate the rustling of the curtains. In Excerpt 3 “there is a transition from the powerful noise of a sea swell to the sound of whispers”. In Excerpt 4, in the “patterning of sibilants hardly a trace of either sound or silence remains” (Hrushovski, 1980: 41). Hrushovski (following Kreuzer, 1955) takes it for granted that in Excerpt 1 the sibilants have a hushing effect. Intuitively this seems right. He also argues that this hushing quality focuses the sound pattern on the meaning of the words “sweet silent”. But he does not explain what it is in the sibilants that invests them with this hushing quality. We shall explore, on a more fine-grained level, how they can express such opposite qualities.

In his “Communication in Poetry”, Fónagy examined the relative frequency of phonemes in six especially tender poems and six especially aggressive poems by four poets in three languages (Hungarian, German and French). Most phonemes occur with the same frequency as in general; but the nasals and liquid [m, n, l] occur more frequently in the tender poems in all three languages, whereas the voiceless plosives [k, t] occur more frequently in the aggressive poems. [r] is aggressive in Hungarian and to some extent in German, but not in French. His method is used today frequently in research, but Fónagy’s use differs from the more recent uses in several respects. Most importantly, he did not assume some rigid iconic relationships between specific speech sounds and emotions where one may predict the emotional quality of the poem from the recurring speech sounds, as some present-day researchers do (e.g. Auracher, Albers, Zhai, Gareeva, & Stavniychuk, 2011). Rather, he probed into the possibility that there may be some significant correlation between pairs of opposite emotional qualities and pairs of opposite phonemes (or groups of phonemes). This was a ground-breaking idea at his time. He did not regard his findings as the “inmost, natural similarity association between sound and meaning” (Jakobson & Waugh, 2002: 182), but as possible examples for a principle.

Tsur, in his earlier works (e.g. Tsur, 1992), went one step further beyond Hrushovski’s and Fónagy’s works. For instance, Hrushovski defines expressive sound patternsas follows: “a certain tone or expressive quality abstracted from the sounds or sound combinations is perceived to represent a certain mood or tone abstracted from the domain of meaning”. Tsur asked the question, how can “a certain tone or expressive quality [be] abstracted from sounds or sound combinations”. In his answers, he relied on distinctive features, and on speech research done mainly at the Haskins Laboratories. The present article provides the answers to such questions as part of a comprehensive theory.

Cognitive Theory

Structural Model of Speech Sounds

In this article, we shall point out the complexity of phonetic symbolism at several levels, and propose a cognitive mechanism that may handle it. The basis for our theoretical account is a structural model of speech sounds: we assume that speech sounds are bundles of features, on the acoustic, articulatory and phonological levels, and that the various features may have different expressive potentials. Thus, we claim that the various phenomena related to phonetic symbolism result from the way speech sounds are coded and organized in our mental database. Here, we focus on the features of consonants.

Consonants can be abrupt: plosives (p, t, k, b, d, g) or affricates (as ts [in tsar), dž [in John or George], or pf [in German pfuj]); or, they may be continuous, as nasals (m, n), liquids (l, r), glides (w [as in wield], or y [as in yield]); or fricatives (f, v, s, š [as in shield]).[2] Continuous sounds may be periodic (nasals, liquids, glides) or aperiodic (fricatives). In periodic sounds, the same wave form is repeated indefinitely, while aperiodic sounds consist of streams of irregular sound stimuli. Consonants can be unvoiced or voiced. All nasals, liquids and glides are voiced by default. Voiced plosives, fricatives and affricates (e.g. b, v, ž, and dž) consist, acoustically, of their unvoiced counterpart plus a stream of periodic voicing. These are objective descriptions of the consonants; all language-users have strong intuitions about them, but frequently they cannot put their finger on precisely what is the object of their intuition.

The structural model described above organises consonants in our mental database in terms of acoustic features. We believe that it is the acoustic level that best accounts for the emotional and imitative aspects of sound-symbolic effects (see also: Aryani, Conrad, Schmidtke, & Jacobs, 2018; Knoeferle, Li, Maggioni, & Spence, 2017; Marks, 1975; Ohtake & Haryu, 2013; Ultan, 1978). Accordingly, we will use this organisation to account for evidence in the study of phonetic symbolism. Note that the proposed model relies on categorical acoustics features (e.g. abrupt/continuous). However, some studies explain phonetic symbolism in terms of continuous acoustic features, such as pitch and intensity (Aryani et al., 2018; Knoeferle et al., 2017). Here we assume a categorical acoustic theory of phonetic symbolism, but keep in mind that a continuous theory of phonetic symbolism can be perfectly consistent with ours.